This article collects learnings I made while collaborating as a service designer for BloodLink, mainly at a pilot we ran in India in June 2018.

Blood donation in India

Many countries in the West fulfil their blood demands through voluntary donations. This is not the case in India, where there is not enough blood supply and a significant amount of the blood need is covered with replacement donation.

Meet BloodLink

BloodLink is an Indo-Danish social enterprise. They wish to take the responsibility of finding blood out of the hands of the patient by connecting blood banks and hospitals through digital tools.

The startup is currently working on a service that connects companies and blood banks to organise donation camps. A team embarked to India to be present at 6 donation camps. As the designer in the team, I was on charge of carrying out intensive research during the camps, ideating on how to increase donor count, frequency of camps and working on new value propositions for BloodLink.

Welcome in India

Indians and foreigners

Being a foreigner researching in India can make some things easier. I have found that, more often than not, Indians are curious to talk to foreigners and compare how things work in different countries. In this project I have often been perceived as an external, non judgmental figure and this has made it easier for people to speak up. Candour can sometimes relax and uptight atmosphere.

Lack of privacy is normal

In this country people are used to having a lot less private space than we do in in the west. Literally, spaces in cities are crowded. Figuratively, Indians can ask personal questions to someone they’ve just met and this is totally acceptable. Things that had been crucial in other cultures, such as warming up and small talk before the interview, or having a private space to talk, were less important in this context as they are in the west.

Fear of disappointing

In India people can be extremely concerned with displeasing others, being respectful and also with saving face. This trait manifests in them finding it very difficult to say “no”. This is crucial to handle when doing research. More than in other cultures, your interviewees will try to guess what you want to hear and answer accordingly. So, more than ever, the researcher needs to show no personal opinion whatsoever about the subject of research. Conventional feedback gathering just doesn’t work.

Hierarchies and processes

Indian companies have a strict hierarchy and bureaucracy, sometimes even hard for acquainted locals to navigate. It is common in organisations to find that the person holding the title for a certain job delegates everything to an assistant person, because they are in reality performing another job. When researching with employees, it is key to identify who is your real user, regardless of the title they hold, and afterwards correctly navigate the hierarchical structure to get access to the person in question. You can’t just go directly to the person you want to talk to; it is expected that you ask permission to their superior for their time. I have found this structure is similar to conventional big companies in the west.

When researching with employees, it is key to identify who is your real user, regardless of the title they hold

Trust

To show respect and provide visibility to superiors in companies, you will often need to interview them, and then get access to their subordinates. Subordinates will not cooperate if they don’t have outright approval from their superiors. And even in cases where the superior has given approval, if you have not succeeded at providing a good impression to the superior, or they feel your activity is a threat in any way, your research session may not happen at all. When researching in businesses, if you’re too acquainted with the subject, you can be perceived as a menace; if you’re too inexperienced, you may be taken advantage of.

A reflection on our methods

I learned to be genuinely economic with design tools and outputs, making sure any efforts polishing a presentation were saved for those things to be shown to the outside of the team. Startup world is ridiculously fast-paced and superficial, just pick the best cherries to showcase, and don’t bother going to the detail. Nobody cares, just focus on the basics and make them crystal clear.

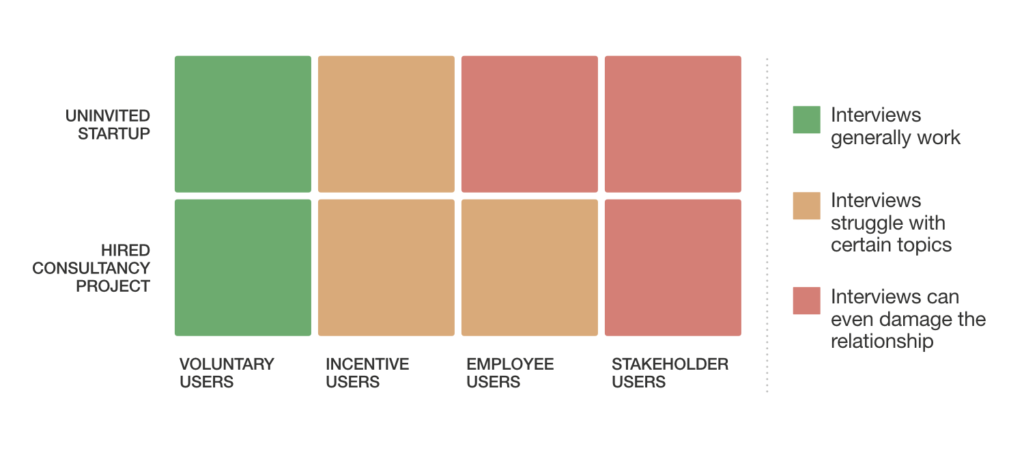

The conventional research tools we use are tailored for design consultancy

Researching in a place where you’re not invited

The conventional research tools we use are tailored for design consultancy. They were born and have mostly evolved in that environment; their timings, resources, procedures, match those very specific business circumstances. When it comes to interviews, resistance to this method grows as we move away from this environment.

As opposed to consultancy projects, in a start up, you find yourself needing to do research with organisations and people that often have no direct take in what you are doing. There are many reasons for people’s resistance and they are all logical. In this project I encountered employees that had come to donate due to peer pressure and found it hard to be honest with me. Donors that didn’t understand what BloodLink was and why we asked so many questions. Professionals in the blood sector that were not so sure of our good intentions and feared our competition. People who had their own hidden agenda, making it for us impossible to figure out what was true and what not.

There are many reasons for people’s resistance and they are all logical

Dropping the notebook

When time came for our last donation camp I had talked to around 40 people of many different profiles. I had identified many patterns and opportunities. I had also given up on some sensitive topics that blood bank staff just shied away from. Once at the camp I dropped the notebook and enjoyed casual chatting with the blood bank comrades. Then, at an unusual moment of quietness, the blood bank member I was talking to just opened up. They answered all the questions I had pending, without me formulating them. Looking back, I think it was a mix of several things that made this happen. The trust we had built with this particular blood bank, over several camps and meetings. Their seniority in the field and self confidence, and, probably, my genuine interest, beyond the research objectives, beyond the project.

Service design fit with the challenge

From a Service Design point of view, the challenge of improving blood donation in India is a Pharaonic one;

- A complex constellation of stakeholders: donors, patients, families, hospitals, blood banks, NGOs, public institutions, CSR & private companies.

- A highly regulated sector, and parallel to it, a big black market that doesn’t follow rules or conventions.

- A shy, mistrustful, hierarchical and wonderfully diverse culture; really complex to grasp.

At the same time, I’ve probably never felt my discipline matched so well the needs of a project. It had all the ingredients that make a Service Design approach necessary in the first instance. This was very rewarding, since nowadays I see Design Strategy and Service Design being used as the Swiss army knife that can tackle any challenge. We can stretch a lot, but no discipline in the world can do absolutely everything.